Kepler the Conniver (1571-1630). Philosophical choice over scientific veracity.

Part 3 of Science as Philosophy. Kepler's 'stolen data', models and philosophies.

Henri Poincaré: “A great deal of research has been carried out concerning the influence of the Earth’s movement. The results were always negative.” (1901 in La science et l’hypothèse, Paris, Flammarion, 1968, p. 182)

Sir Fred Hoyle: “…the geocentric theory of Ptolemy had proved more successful than the heliocentric of Aristarchus. Until Copernicus, experience was just the other way around. Indeed, Copernicus had to struggle long and hard over many years before he equaled Ptolemy, and in the end the Copernican theory did not greatly surpass that of Ptolemy. (Fred Hoyle, Nicolaus Copernicus: An Essay on his Life and Work, 1973, p. 5)

Introduction

We will split the analysis of Kepler into 2 parts to keep it short. In this post we will discuss the background and philosophies which provide the foundations for Kepler’s amendment of Copernican theory. In the next post we will analyse his claims and ‘proofs’.

Scientism

Copernicus provided no proof for his heliocentric theory of cosmological organization. The 2 men quoted above knew this. His system possessed more ellipticals or quants than the Ptolemaic and his underlying assumption that planetary motions followed circles within a ‘crystalline sphere’ was wrong. The accuracy of the Copernican system is inferior to that of the Tychonic. Copernicus the Confused’s primary work De Revolutionibus, was poorly written, devoid of factual evidence and based largely on Platonic religio-philosophy. Another example of Scientism.

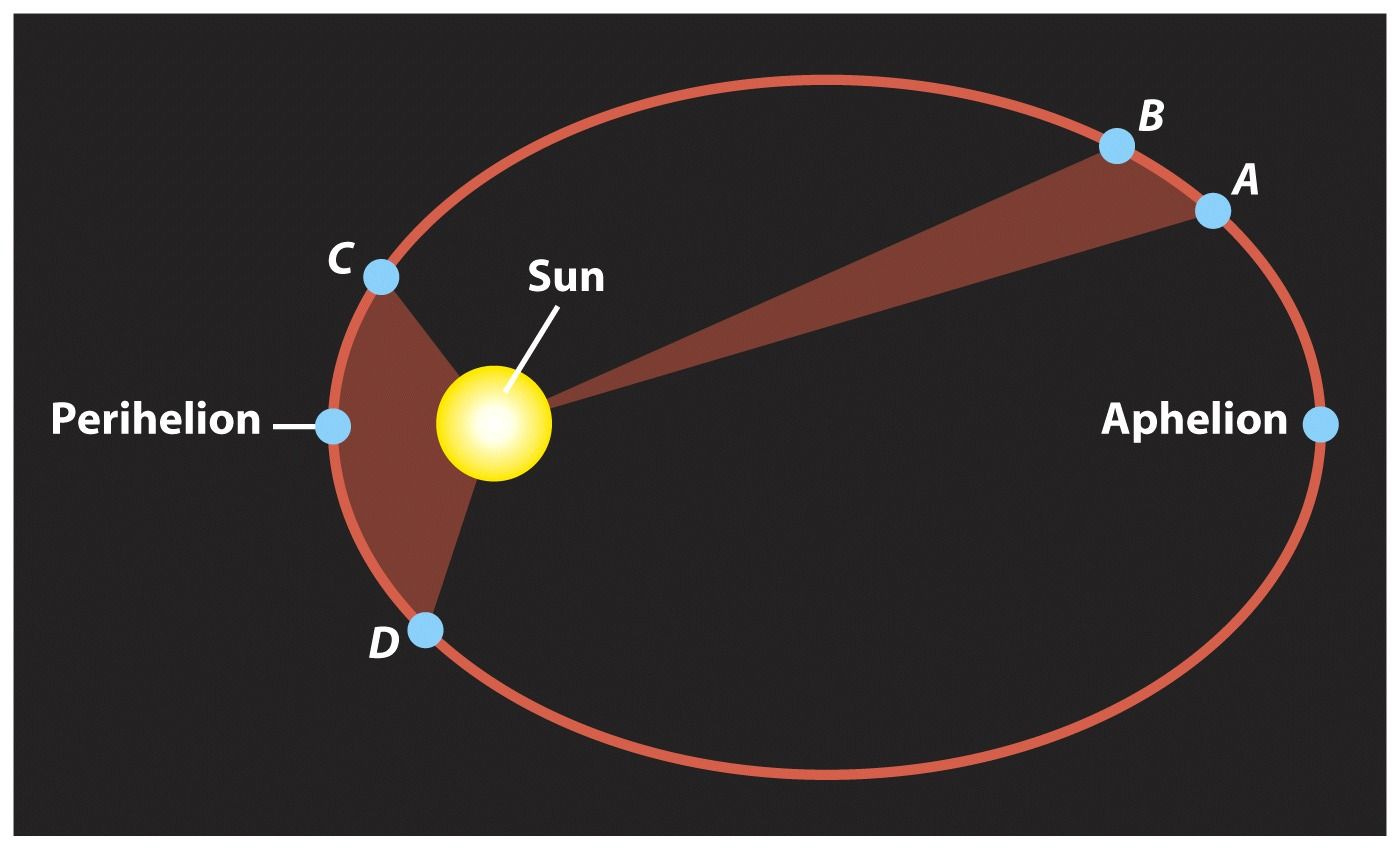

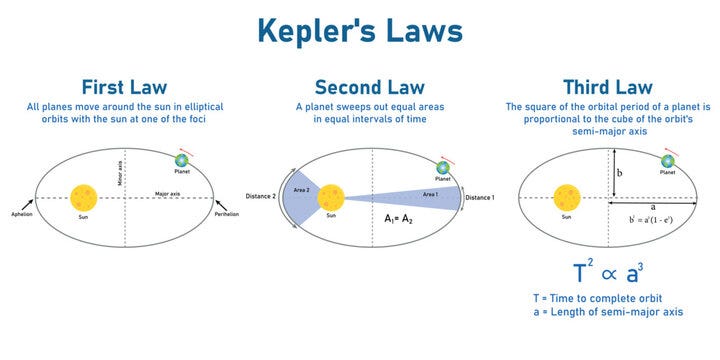

In the early 17th century, it was Kepler who rescued the detritus of heliocentricity from the Copernican confusion. The earnest German Lutheran developed an elliptical model for the orbits of the planets, basically imitating Ptolemy. This seemed to make things run more logically for the heliocentric system. Kepler presented these ideas in his famous work Astronomia Nova in 1609, at about the same time that Galileo began agitating for heliocentrism, although like Copernicus, he provisioned no proof nor even rational arguments for the system.

In 1577 Tycho Brahe discovered and charted the course of a comet, proving that Copernicus’ ‘proof’ for ‘crystal spheres’ in outer space, within which planets rotated around the Sun was false. The comet circling the Sun would have crashed into the spheres. Copernican theory was therefore invalidated. Enter Kepler.

Your philosophy matters

Kepler performed his work in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His mother was tried as a witch and a relative was executed as one. Though pious and serious Lutherans, it appears that the Kepler’s dabbled in black magic and the occult (J. A. Connor, Kepler’s Witch, 2004, pp. 275-307). Such an attitude and predisposition would of course affect this astronomical work. Kepler, like Copernicus, also believed in the Platonic worship of the Sun.

Kepler’s Rationalist-Platonic philosophy was paramount. In one passage he described his veneration of the Sun: “Who alone appears, by virtue of his dignity and power, suited…and worthy to become the home of God himself, not to say the first move.” (Kepler, De Harmonice Mundi, 1619). The worship of the Sun as the prime ‘cause’ in God’s universe and an expression of God itself was common in the 16th and 17th centuries. The above phrase is not unique to Kepler or to early Copernicans. They truly worshipped the Sun.

Kepler was also a Grecophile. He was heavily influenced by Greek thought, and particularly the Pythagorean concept of the harmony of the spheres. Physics today, in areas such as quantum mechanics, still hearkens back to Pythagorean ‘symmetry’. Kepler employed the concept of harmonic ratios to develop his third law of motion where the cube of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the square of its distance from the Sun. Kepler attributes divinity to this complex geometry: “Geometry, coeternal with the divine mind before the origin of things, God himself (for what is there in God that is not God himself) has supplied God with the examples for the creation of the world” (Johannes Kepler, De Harmonice Mundi, 1619).

Cosmological Mysteries

Kepler’s third law of motion was based on ancient Greek maths. In his first book on astronomy in 1596 entitled Mysterium Cosmographicum, Kepler defended the Copernican system by asserting that the planets’ orbits were tied into the ratios of the Platonic solids. In this book Kepler states that each of the five Platonic solids can be encased in a sphere and thus produce six circular layers corresponding to the six orbits of the known planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

By a precise ordering of the solids: octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, and cube, Kepler showed that the spheres could be made to correspond to the orbits of the planets. However, this meant jettisoning the entire system of Copernicus except 2 axiomatic claims; that the Earth rotates and revolves, and that the Sun is still.

Kepler had a difficult time explaining why and how the planets would orbit a motionless Sun. The Sun’s lack of motion is still unexplained within cosmology. After reading William Gilbert’s book on magnetism in 1600, Kepler offered the solution that the magnetic pull of the Sun was responsible for the attraction of the planets and their orbital motion. This has long been discredited of course. During this period Newton was still in the future. Copernican theology had and indeed still has a problem. Why do planets orbit the Sun in such a regular and timelessly accurate pattern? (Cohen, Revolution in Science, pp. 125-126)

Brahe’s influence

Tycho Brahe was a contemporary of Kepler and the greatest of astronomers during that period. His detailed charts and observations over 40 years, compiled in the world’s first observatory in Denmark, were unique. Modern telescopic observation reveals that, without ever using a telescope, Brahe’s star charts were consistently accurate to within 1 minute of arc or better. His observations of planetary positions were reliable to within 4 minutes of arc, which was more than twice the accuracy produced by the best observers of antiquity.

With this data Brahe proposed the Tychonic system, namely a mix of geocentricity and heliocentricity. The Earth is immobile, and the Sun orbits the Earth, and the planets orbit the Sun. Using modern scientific ‘postulates’, the Tychonic model explains the ‘phenomena’ at least as well and probably better than the heliocentric.

Kepler worked for Brahe for about one year. It was with Brahe that Kepler accessed the pot of gold, namely Brahe’s indefatigably detailed charts. Brahe never formerly granted Kepler access to his charts. It is likely that Kepler stole or copied the information. There are whispers that he murdered Brahe to get a hold of this sacred work (mercury poisoning, disputed and no one will ever know).

Kepler could have combined his maths skills with Brahe’s observations and ‘proven’ the Tychonic model. But this would only reinforce the great man’s mythology. How much better would it be for Kepler to ‘prove’ his own, rather novel view of Copernicanism using Brahe’s own data, and displace the great man and become a greater man?

“And Tycho knew that the gifted Kepler had the mathematical wherewithal to prove the validity of the Tychonic [geocentric] system of the heavens. But Kepler was a confirmed Copernican; Tycho’s model had no appeal to him, and he had no intention of polishing this flawed edifice to the great man’s ego” (Alan W. Hirshfeld, Parallax: The Race to Measure the Universe, 2001, pp. 92-93)

Without Brahe’s charts, Kepler would have been just another 17th century astronomer struggling to make a living by reading astrological horoscopes and making inane predictions of the future a la Nostradamus. Kepler possessed little evidence upon which to base his theory regarding the motions of the planets, independent of what he stole or ‘borrowed’ from Brahe. No Brahe, no Keplerian system.

This statement is true given that the mirror opposite of Kepler’s model is the Tychonic system. Whatever improvements Kepler made to the Copernican system were automatically true for Brahe’s, even if Kepler failed to apply them. In Brahe’s model the Sun is in orbit around the Earth, while all the planets orbit the Sun.

Therefore all the distances, geometry and velocities of the Kepler-heliocentric system are identical with that of Brahe’s. For example, in answer to Galileo’s complaint about Venus, in the Tychonic system Ptolemy’s deferent (an epicycle or geometric explanation of motion), of Venus is now outside the Sun, and thus all of Venus’ phases can be seen from Earth. There is therefore no difference in ‘science’ or ‘maths’ between the Keplerian and the Tychonic models. Both ‘save the phenomena’.

Interpreting the data

Kepler’s geometrical modification didn’t prove that the discredited Copernicus and his Sun-centred, crystalline spheres of a system was accurate. It merely revealed Kepler’s preferences, since he knew that, if the same elliptical modifications were given to the reigning geo-helio-centric model of Tycho Brahe, they would have shown heliocentrism to be merely an alternative system, not a superior one.

By the time of Kepler, most astronomers understood, unlike Copernicus, that planetary orbits are not perfect circles though they may be very close to being just that. When Kepler analysed the orbit of Mars, he found that its deviation from a circle was only one part in 450. This is the same deviation Ptolemy found for Mars, which was demonstrated by his equant. In other words, Kepler’s system is no more accurate or predictive than even the Ptolemaic (Owen Gingrich, The Book that Nobody Read, p. 53).

Kepler, like Copernicus and like Galileo, used his philosophical and occultist philosophies as a basis for his interpretation of the data. Kepler desired to outdo the ‘great man’ Tycho Brahe. He understood quite well the advantages which would accrue to himself if he could push the Copernican model. Besides ego and personal profit Kepler had a philosophical imperative. He demanded that the Earth move around the Sun as part of his Sun-worshipping theology but also as a part of the Earth’s great adventure in space, a moving platform so to speak, from which the human can view the magnificence of God’s creation:

“For it was not fitting that man, who was going to be the dweller in this world and its contemplator, should reside in one place of it as in a closed cubicle: in that way he would never have arrived at the measurement and contemplation of the so distant stars, unless he had been furnished with more than human gifts…it was his office to move around in this very spacious edifice by means of the transportation of the earth his home and to get to know the different stations, according as they are measurers, i.e., to take a promenade so that he could all the more correctly view and measure the single parts of his house” (Kepler’s Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae, 1618, 1620)

This is a very queer expostulation from a ‘scientist’. The Earth should move in the heavens, as an owner moves in his house, room by room, to better appreciate the entirety of his dwelling? Yet Kepler could not explain why or how the Earth moved and why it would move in the same pattern. The peregrination of the Earth is therefore unexplained and according to his model, monotonous and rather limited. It affords no great opportunity for ‘adventure’, or ‘room’ analysis.

In the next post we will discuss the ‘proofs’ for Kepler’s claim and for Copernicanism as an amended model. Not surprisingly ‘the science’ understands perfectly well that the Copernican model is a philosophical choice, not a scientific ‘fact’. This of course is never taught or discussed. All hail.

==Posts in this series