Scientism and Special Theory of Relativity. The paradigm is ending. Too many issues.

STR is one of the most striking cases of $cientism and the blind acceptance and faith in abstract models.

“One of the most striking characteristics of Einstein is that even in those papers where he worked out the profoundest theoretical principles and theories, such as in the 1905 paper about the special theory of relativity, he did not finish without at least glancing around for possible verifications of their empirical consequences.” (Klaus Hentschel, ‘Einstein’s Attitude Towards Experiments, Testing Relativity Theory 1907-1927’, 1992).

For STR and much of ‘the science’ mathematics and their elegant explanations, backed by some qualitative proofs took precedence over physical reality. As the ancients, the scholastics and Pierre Duhem would have said, maths were employed to ‘save the phenomena’ with abstract calculations and metaphysics in lieu of physical proofs.

Previous posts

An overview of Special Theory of Relativity (STR)

An introduction to the underlying maths of STR

Key scientists and actors within the STR domain

James Webb Telescope observations which refute parts of STR and the Big Bang

Herbert Dingle’s unanswered clock paradox and the inherent contradiction within STR

Background to this post

The theory of relativity has been debated for over one hundred years. Contrary to what we are told there has been and there still are, plenty of scientists and analysts who remain unconvinced by the abstract mathematics of Einstein and his STR and the lack of physical proofs. It is a theory in crisis.

While febrile, STR does convey an important but hard to prove concept of time dilation. Namely that the clocks in space go much faster than on Earth, meaning that space time age is much longer than Earth age. From many perspectives this seems plausible and reasonable. This idea is very difficult to prove without performing interstellar experiments.

For the rest of STR There is plenty to critique about the ‘laws’ of STR, which are rarely mentioned within Scientism or ‘the science’. Previous posts have summarized STR, its maths and surfaced some issues. This continues with the critique and focuses on the key question of the ‘ether’.

What is STR trying to do?

STR is an attempt to correct Newtonian laws on gravity and ‘save’ the Maxwell-Lorentz equations on motions and the speed of light. Einstein wanted a ‘unified’ theory where Newton’s law of inertia was married to the equations of Maxwell-Lorentz. To do this he needed to remove the ‘ether’ (more below) and update the theories for his idea of ‘relativity’, or the difference in the phenomena of speed and motion between objects and their clocks, based on an observer either static, or in motion with the objects in question (Resnick, 1972).

As with Maxwell’s obstruse and endless pages of symbology and maths, STR is at its core a mathematical edifice which is entirely theoretical, not physical. Contrary to ‘popular science’ little physical proofs exist for the Maxwell-Lorentz theorems or for Einstein’s STR theory which is largely a modification of Lorentz’s theorems with the ether removed.

Having said that, Lorentz’s theory is far more empirical than Einsteins. It should also be stated that Einstein’s famous formulation of E=Mc2 in which energy and matter is interchangeable seems to be correct, but is largely borrowed from Maxwell and others. There does exist many critics of this equation who maintain it is false. In any event this famous ‘law’ does not belong only to Einstein, nor to STR. People who use this as proof of STR do not understand that independently and long in advance of Einstein and STR, energy and mass equalisation proofs were forwarded and developed. E=Mc2 does not prove STR whatsoever.

A list of problems with STR

We can list issues with STR as given by many scientists and researchers who have delved into the theory. Literally hundreds of scientists and researchers in the past century have heavily critiqued the validity of STR. But no one has heard about this. The issues include:

1. Mathematical abstraction, where maths replace physical proofs

2. Impossibility to prove or disprove the mathematical arcana given their long, complex and tautological nature

3. Maxwell’s equations were not understood by many and pace Pierre Duhem and others, might well be wrong

4. Lorentz’s equations are not understood by many and pace sundry critics, might well be wrong and further, Einstein accepted his maths which only work with an ether, yet rejected the ether

5. Few if any observations confirm Lorentz’s theories though the qualitative and quantitative proofs for this theory heavily outweigh that of Einstein’s

6. Michelson-Morley’s experiments which ‘disproved the aether’ did not so thing, they disproved the motion of the Earth around the Sun

7. The aether used by both Maxwell and Lorentz could be valid based on experiments from the past 100 years (more below)

8. If the aether in any form, with any density is valid, STR by default is invalid

9. Einstein’s STR suffers from the clock paradox and does not have empirical physical proofs to support the maths

10. The observed time-dilation effect in atomic clocks could be caused by a physical effect of the ether-wind on electron’s orbits inside the clocks (more below)

11. Space-Time dimension (4th dimension) is unproven and unlikely given that time is outside of space and is a metaphysical construct

12. The production of multiple time concepts as evidenced by Harald Nordenson (1922-1969) would invalidate STR

13. The speed of light might well vary within space, negating much of STR which assumes is a constant rate in a vacuum applied to the universe

14. Shadow gravity is a better explanation of how gravity would function than Newtonian gravity, which is a core component of STR (more below)

15. The Big Bang theology is incorrect, much of it premised on STR with ‘dark matter’ and ‘dark energy’ simply replacing Einstein’s fudge namely his ‘constant’ which he invoked to stabilise the universe and resolve issues with Newtonian gravity

Any of the above would disprove STR (Smarandache 2013). Each could fill and has filled, a small book. An example is that of the ‘aether’ or ‘ether’ which is simply accepted by those in cosmology and physics to not exist. But like much of ‘the science’ this is incorrect, resting on unproven assumptions and very outdated experiments and ideas. The ether is a classic case of where a few people make decisions based on models and contentious experimetation and the rest of the industry simply accepts this truncated analysis as a law and builds yet more mathematical models and explanations upon this flawed foundation.

Definitions and the Aether

Defining terms is important. Terms related to ‘ether’ include:

· Aether or Ether: existence of a medium, a space-filling substance or field as a transmission medium for the propagation of electromagnetic energy or light

· Transformation of coordinates: The process of converting the coordinates in a map or image from one coordinate system to another, typically through rotation and scaling

· Transverse: Set crosswise against an axis

· Transverse wind: A wind crosswise against the axis

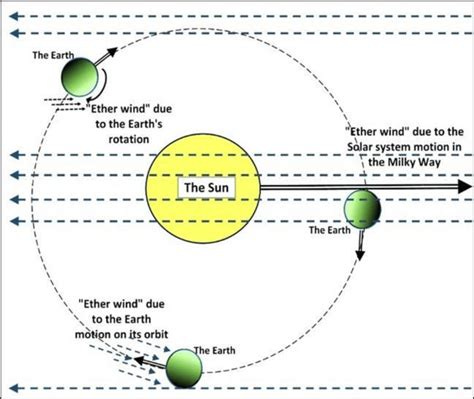

· Ether-wind: Wind generated by the moving Earth in respect to its ether

· Entrained ether: Ether wind is trapped and dragged by moving matter

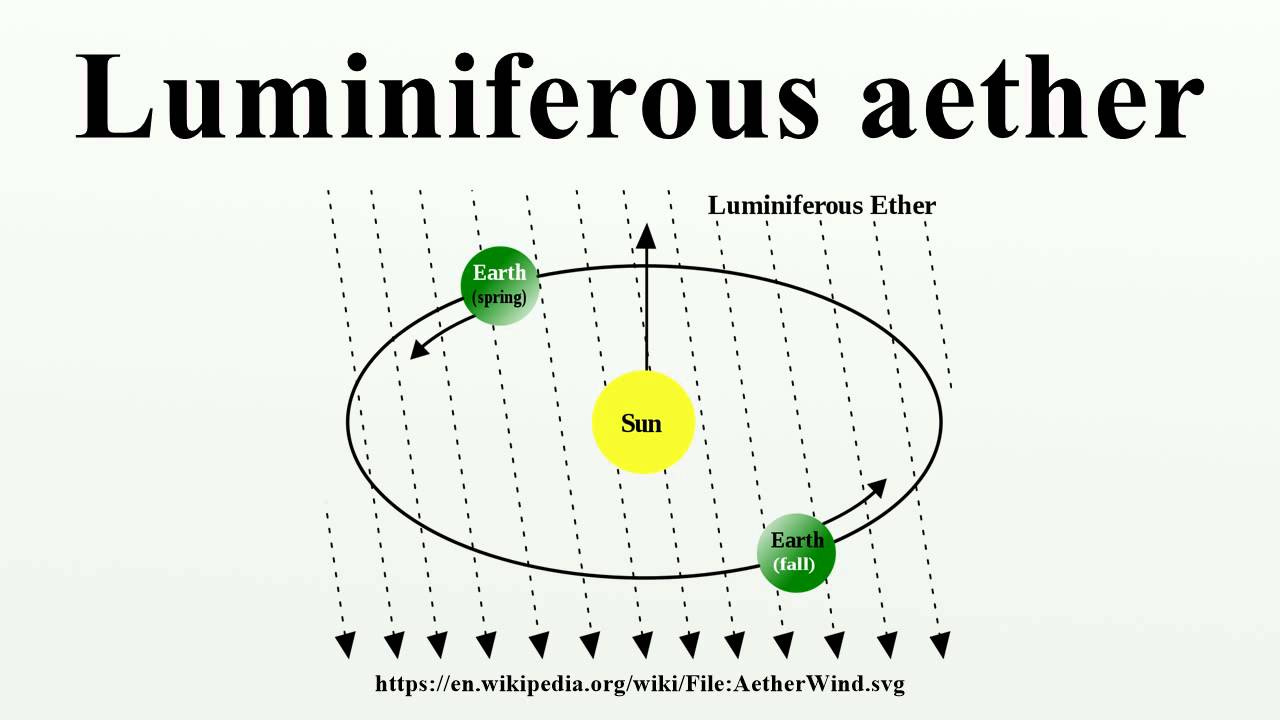

· Stellar ether: Space ether which can be luminiferous or emit light

Ether Background

In the 19th century the concept of an aether was widespread. This was due to observed phenomena. In Newton’s particle model for light, he and others noticed an ‘aberration’ sometimes called the ‘raindrop’ effect. With raindrops or light refraction, a transformation of coordinates into the frame (location and map) of the moving observer is needed to describe the observer’s conception of the phenomena in question.

The maths of this observation can be summarized (Andrade 2005).

· An observer is moving with the speed u transverse to light with speed c

· The direction of light, for this observer changes to that of an angle arctg(u/c)

· The speed of light is changed to (c2+u2)1/2

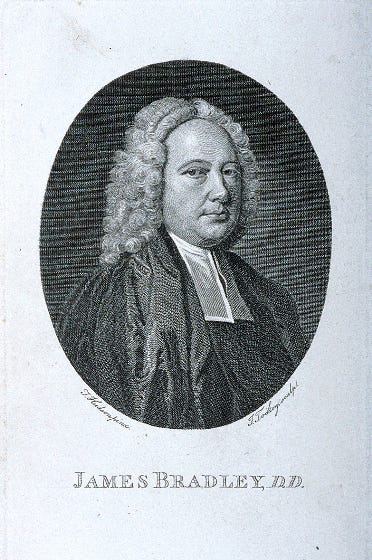

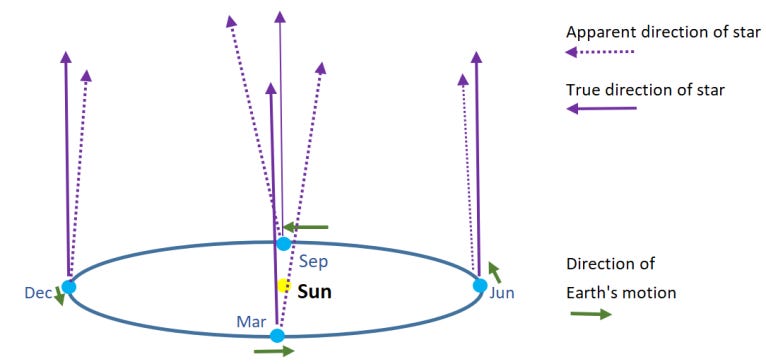

In this scenario, the Observer’s motion u, creates the illusion of a changed direction to some fixed position. In 1725, the English astronomer James Bradley, observed what he termed ‘stellar aberration’ and explained such phenomena as given above, in simple terms. Bradley believed that stellar aberration is the apparent shift in the position of stars due to the motion of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun. As we shift with the Earth and view the stellar objects there is an aberration and refraction.

This observation provided one of the earliest purported pieces of evidence for the Earth's motion. It is wrong of course as described here and here. Bradley calculated that the apparent positions of stars changed over the course of a year in a cyclic pattern, and he explained this effect by the combination of the Earth's motion and the finite speed of light.

In 1810, François Arago also addressed the same set of issues. Arago sought to measure how light particles were refracted by a glass prism in front of a telescope. He predicted that there would be different angles of refraction due to the different velocities of the stars and the motion of the Earth at different times of the day and year. Contrary to his expectation, he found no difference in refraction between stars, time zones, or seasons. All that Arago observed was normal stellar aberration – as evidenced previously by Bradley (Persson 2011).

Maxwell’s Maxims

During the 19th century Maxwell’s wave model for light (1858) replaced the Newtonian particle model for light. In Maxwell’s model an ether (called the luminiferous aether) was needed, or a medium which interacts with light (unlike dark matter which would be particles or an ether that do not emit light). Two basic theories about the ether existed.

One: there is no relative motion between the Earth and the Ether.

Two: the Earth is moving relative to the ether, and the measured speed of light should depend on the speed of this movement (the ‘ether wind’), resting on the Earth's surface.

The aberration example cited above, using Maxwell’s ideas, could be explained by an ‘ether-wind’ v, instead of by the observer’s motion u as stated by Bradley (Andrade 2005). Many ideas and experiments were erected to test the idea of an ether. In these, no effect of a transverse ether-wind v was discerned. The simple explanation from Bradley, that the aberration effect is due to observer’s speed u (for example a moving Earth, where the observer is viewing stars in a telescope), seemed to be valid for the Newton and Maxwell light models (particle model and wave model). But the transverse ether wind was not what many physicists supported – the idea of a captured or ‘entrained’ ether wind, trapped by matter itself, was the main focus.

Fresnel, Stoke, Planck

In 1818, Augustin-Jean Fresnel proposed that the ether is partially entrapped in matter. In 1845, Sir George Stokes the English evangelical, famous for his experiments and theories on optics and hydrodynamics, followed on from Fresnel, proposing that the ether is completely entrapped within, or near matter. Fresnel's near-stationary theory was confirmed by the Fizeau experiment (1851) but was supposedly disproved by the Michelson-Morley experiment (1887) and the Truton-Noble experiment (1903) which gave negative results. As outlined previously there are plenty of issues with the MM experiment (more below as well). The TN experiment has also been proved fraudulent with recent experiments giving a positive outcome.

A key insight and proof from Stokes building on Fizeau’s ideas, was that the ether was incompressible and non-rotating. This gave Stokes the correct law of aberrations in relation to his particular etheric resistance model. In order to reproduce Fresnel's drag coefficient (and thus to explain Fizeau's experiment) he argued that the ether is perfectly dragged in the medium. That is, the ether condenses as it enters the medium and becomes rarefied as it exits the medium, which changes its velocity. This was a better explanation than Fresnel’s.

Max Planck (1899), supported the idea of an ether, writing to Lorentz that an ether is not incompressible (as Stokes thought), but can be condensed by gravity near the Earth. He argued that this would provide the necessary conditions for Stokes' theory (named the Stokes-Planck Theory). Lorentz rejected this idea, using Fresnel’s theory as a starting point and then pursuing his own idea of ether which was immobile or not prone to change (more below).

Another version of the Stokes model of a drag-ether, was proposed by Theodor de Cudre and Wilhelm Wien (1900). Wien had 2 versions. His first idea was that no relative motion exists between Earth and aether. A second version offered that the Earth does move relative to the aether, and the measured speed of light should depend on the speed of this motion. This ether-wind should be measurable by instruments at rest on Earth's surface (some experiments tried and failed to find such an ether). For example, the ether around the Earth would be completely entrained by the Earth, but only partially entrained by smaller objects on the Earth.

Michelson Morley mistakes

In 1887, to prove or disprove the ether, Michelson and Morley sent information between mirrors to see a second order effect on the two-way speed of light from the ether-wind. They returned a null result. However, they did not disprove the reality that the separation between atoms in a crystal must be controlled by the ether. It is very difficult to see an alternative. The atoms produce static fields in the ether and these fields become dynamic due to the ether-wind (Persson 2010).

This means that information is transmitted in both directions between the atoms with the speed c in relation to the ether. The information flowing between atoms is simultaneous in the two directions, but the flow between Michelson’s mirrors is sequential. This contraction is 2 times the Lorentz-Fitzgerald contraction but is not combined with a time dilation. Therefore, Michelson and Morley’s tests cannot tell us anything about the state of motion of the ether.

Sagnac effect

Light is distributed along a line and not over an enclosed area. Based on this premise an important set of experiments was manufactured by Georges Sagnac (1869–1929), a French physicist and astronomer who made significant contributions to the fields of optics and experimental physics. He was also a vocal critique of STR. In 1913 he reported his eponymous effect, or the phenomenon observed in interferometry when a system is set into rotation. This results in a phase shift between beams of light traveling in opposite directions around a closed loop.

The important point is that the Sagnac effect is an effect of translation. This is because the interferometer (a device which merges two or more sources of light to create an interference pattern, which can be measured and analyzed), compares the phase between two parallel wave fronts and reacts in one dimension only. Detection in one dimension can only detect translation and rotation of the equipment due to the clock-synchronization problem (Persson 2010)1.

The Sagnac effect is quite likely a first order effect of an ether-wind and provides very important information regarding the state of motion of the ether. GPS systems and time dilation are examples of the Sagnac effect (Smarandache 2013).

Michelson’s fraud

In 1925, the Sagnac effect was supposedly refuted by the Michelson-Gale-Pearson experiment which was an update to the 1887 Michelson-Morey experiment. This experiment was different from the usual Sagnac experiment in that it measured the rotation of the Earth itself. Negative results would have been expected if the aether was completely dragged by the Earth's gravitational field, but the results were positive.

Unfortunately, this experiment was incorrect and cannot be replicated and in fact it is likely that Michelson intentionally fabricated his results to align with STR. Michelson had been awarded a Nobel in 1907 for his work on measuring the speed of light. This makes it highly unlikely that his experiment in 1925, which called into question the speed of light and his own Nobel, was going to be forwarded as a conclusion.

Wave fronts

Since the 19th century advanced optical tools including telescopes, resonators, lasers, interferometers, have been deployed to determine stellar, or space ‘aberrations’. The key assumptions are that the wave of light velocity c is a constant and an ether-wind v, sits inside this wave. This means that the ‘wave front normal’ is conserved in relation to changes in the transverse ether-wind (Huygens).

In the instruments listed above, the relevant description of light is: c(1+vc/c).

In this model vc is the component in v that is parallel to c.

When v and c are orthogonal (lines that meet at a right angle) to each other, they are independent of each other.

Using these instruments and based on the list above, the wave fronts are always parallel to the mirrors and the resonators are independent of an ether-wind blowing in the plane of the mirrors and wave fronts (a resonator is a device or system that measures resonance, or the oscillation or amplitude of a system at certain frequencies). Therefore, in Michelson and Morley’s test of 1887, light speed and wavelength moved along the optical axis and were independent of the ether-wind which resides inside the wave fronts. This means that their experiment did nothing to disprove an ether simply calling into question a transverse ether-wind, which was already largely unsupported by the proponents of an ether-wind.

Not an ethereal mistake

The abolishing of the ‘entrained ether’ or embedded ether-wind, by reference to stellar aberrations was a mistake. The direction of light can mean 2 different things (vector and normal to wave fronts summarized above, the Huygens principle).2 When astronomers observe stellar aberration in a telescope, they are using an instrument detecting the normal to the wave front (Janssen, Stachel, 2004).

In essence physicists must explain stellar aberration by means of the transverse component in observer’s motion u instead (Bradley’s insight). The effect of observing a moving phenomenon from a moving platform must be the same, independent of if the phenomenon is a particle or a wave. This gives more credence to the entrained ether concept (Persson, 2010).

An Airy Lodge

In 1871 Sir George Biddell Airy an evangelist, set out to record the change in the direction of light passing through a refracting medium that is moving. This followed on from Fresnel (1818) and Fitzeau (1851). His experiments are replicable.

Airy demonstrated that stellar aberrations occur even when a telescope is filled with water and measurements are taken from the moving Earth (moving medium). This is not what the theory predicts. As with Fizeau, the Airy experiments suggest that light does propagate through dielectic or poorly conducting matter but at a reduced phase velocity. The stellar aberration hypothesis seemed to be disproven (flat-earthers often use Airy’s experiment as proof of geo-centricity and a flat earth).

Scientism of course maintains that Airy’s experiments disprove the ether theory. But this is incorrect if you look at what he did. All Airy did was fill the telescope tube with water and then take star measurements. By default, no drag is involved given that the setup has precious little to do with drag measurement. For instance the Fresnel drag is not involved because Airy, who is the ‘observer’ is moving with the telescope, at the speed of the Earth, so the relative speed is obviously zero. A light beam hitting the water filled telescope will need to reach a final point somewhere in the tube to be observed, given that Airy was not immersed in water.

Oliver Lodge (1890) also conducted experiments in the 1890s seeking evidence that light propagation was affected by being near large rotating masses but found no such effect. Lodge still believed the ether existed but that it was difficult to find. His 1925 book ‘Ether and Reality’ provides an overview of his experimental evidence for an ether, where he maintains that the ether accounts for the movement of light, gravity and even heat across a vacuum. He did however refute the stellar aberration concept (Hunt 1986).

Lorentz’s Ether, rubbished by Einstein

Lorenz felt himself forced to abandon Stokes' hypothesis and chose Fresnel's model as a starting point. Although he was able to reproduce Fresnel's drag coefficient in 1892, in Lorenz's theory the drag coefficient represents a change in the propagation of light waves rather than a result of ether entrainment. Therefore, Lorentz's ether is completely still or immobile. Other experiments which seemed to confirm Lorentz's ether include Röntgen (1888), Coudres (1889), Königsberger (1905), and Trouton (1902).

Einstein hated the entire idea of an ether. It is unclear why the animus. He viewed the ether as a gordian knot and did not bother to investigate, test or disprove the various ether theories in existence. He simply took Alexander’s sword and sliced the ether-knot in two, tossing it away (Darrigol 2000). Einstein never performed an experiment to disprove the ether, and rejecting the ether is at the core of his theory.

Gravity, Ether and particles

Einstein’s STR is in part based on Newtonian gravity and laws of motion. It has been proven that a gravitating body absorbs a small amount of gravity particles passing through the body. Nicolas Fatio (1690) and Georges-Louis Le Sage (1748) created a model of gravity that was termed ‘push-gravity’ or ‘shadow-gravity’. Their models were supposedly fraught with problems. However, recent research has proven that they were probably right and that their gravity models do a better job than Newton’s in explaining how gravity works.

The acceptance of ‘shadow gravity’ would be a stupendous development with the implication that an ether is the missing part of the particle flow that follows the active mass. This would indicate there is a shadow like effect that is entrained by matter, not the ether per se. This would be important given that a small difference in the number of ether particles moving with the speed c causes an average vertical velocity of -7.91 km/s. This is the cause of gravity (J. E. Persson, 2011). In other words, gravity, which is now a ‘black box’ that few can explain, might have a real and testable physical causation.

GPS proves an ether

An ether effect is demonstrated in an obvious way by GPS systems. A global positioning system is rendered based on the one-way speed of radio signals and triangulation. Universal time – a constant requirement in software and systems – can be accomplished through a circumvention of the synchronization problem and compensating for the Sagnac effect mentioned above. This is done in a not-rotating frame translating with the speed of the Earth’s center. Confirmation of an ether wind measurement has been satisfied by many and easily explains how a GPS works (example Dr C C Su, 2001). There is no evidence whatsoever that STR has played any role in the development of GPS.

Further, it is also acknowledged that every planet is surrounded by a field which is dependent on the distribution of matter. This means that the entrained ether is the correct ether model. A very important support for this idea is the fact that planets can move in orbits without being retarded by friction. The ether provides no resistance to velocity, only to changes in velocity (acceleration) by inertia. This obvious fact is usually missing when planetary motions are discussed (Janssen,Stachel 2004).

Bottom Line

The paradigm of STR, like that of the Banging religion, must be near its life cycle end. Money, power, egocentricities, recognition, getting published, speaking tours, the endless awards and self-congratulations within a small circle, and a vested interests in the reigning paradigm (pace Thomas Kuhn) keep it alive. The issues outlined in this post are real and obvious.

A search of the academic and scientific research will return literally hundreds of scientists and researchers in the past 100 years, who for various reasons, did not, or do not believe in STR and have experimental proof supporting their arguments. These criticisms are rarely heard and more rarely voiced inside the mainstream ‘science’ media. It is a truism that the entire history of STR from its inception and blind, almost ignorant and faith-filled acceptance to its current maintenance as religious-gospel, is a classic case example of $cientism. If and when STR is largely overturned much of cosmology will need to be rewritten.

====

1The Sagnac effect is related to the state of motion of the ether. Since the effect is translational, the same effect must exist in a straight line of length L moving with the speed v in its own direction in relation to the ether. This means Δt=vL/c2 (one way). Ignoring this important fact has resulted in explaining away Δt as production of ‘local’ time. Such a production of multiple time concepts refutes the theory of relativity according to Nordenson (John Erik Persson).

2Light direction - one concept is the beam of direction defined by the vector sum c+v. Another concept is the normal to the wave fronts inside that beam defined by c(1+vc/c) where vc is the component in v that is parallel to c. In the last definition the ether-wind blowing inside the wave fronts is irrelevant (Nordenson, 1969).

====

Sources

George Biddell Airy (1871), “On a supposed alteration in the amount of Astronomical Aberration of Light” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Volume XX No. 130, (Art. IV), pp. 35–39

Roberto de Andrade (2005) Mechanics and Electromagnetism in the Late Nineteenth Century: The Dynamics of Maxwell's Ether.

Oliver Darrigol, (2000), Electrodynamics from Ampére to Einstein

Bruce Hunt (1986), Experimenting on the Ether: Oliver J. Lodge and the Great Whirling Machine Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, Vol. 16, No. 1 (1986), pp. 111-134 (24 pages)

M. Janssen, J. Stachel, (2004) The Optics and Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, Max Planck. Inst. Hist. Sci.

Oliver Lodge (1925) Ether and Reality (delves into metaphysics as well)

G B Malykin, Usp Fiz Naut 170 (1325-1349) (2000); Phys Usp 43 (1229-1252) (2000)

H. Nordenson, (1969) Relativity, Time and Reality, Georg Allen and Unwin Ltd., London.

J. E. Persson, (2010) The empirical background behind relativity, Physics Essays Vol. 23, (634-640).

J. E. Persson, (2011) The Great Confusion: Wave or Particle?, .www.lulu.com

Robert Resnick (1972) Wikibook: Special Theory of Relativity, Basic Concepts of Relativity and Early Quantum Theory

C. C. Su, (2001), J. C. Eur. Phys 21, 701-715

Kenneth Schaffner (1972), Nineteenth-century aether theories, Oxford

Florentin Smarandache (2013) Unsolved problems in special and general relativity

Edmund Taylor Whittaker (1910), A History of the theories of aether and electricity